I bought a Harman Kardon Citation II Tube amplifier (my forth I’ve owned over my lifetime) from eBay. As is common, the previous owner chose not to, or didn’t know, the condition of the amplifier when he sold it. I took a risk and bought it, as it looked to be in nice shape and I was taken in by the included tube cage. Upon receiving it, I opened the bottom and measured the transformers. One screen grid lead had high and inconsistent readings. At first it was 20 kOhms, then it tropped to 4 kOhms, then down to about 50 Ohms, and back up. Wiggling the wires coming out of the transformer didn’t change the reading at all. I knew the worst, there was a fault somewhere inside the metal can, which is filled with tar.

I really had nothing to lose, so I decided to get out the torch and see what was inside the can. I didn’t think I could actually fix the transformer, but not trying is admitting defeat.

The trick is figuring out how to get into the potted case to the transformer itself. The top and sides of the can are drawn and are a single unit. The bottom is a second piece and I suspected was stamped so that it had short sides that nested inside the body of the can. The seam is then soldered.

It was unclear if the mounting studs for the transformer can also passed through the transformer laminations. If the mounting studs also held the transformer, then the top of the can would slide off the transformer, if not, then the bottom would come off by itself. I scritched and scratched around the mounting studs with a scribe to try to find a gap which would indicate that the bottom plate is slipped over the studs late in manufacturing. I didn’t find any such gap, so I assumed that the studs were press fit into the bottom cover.

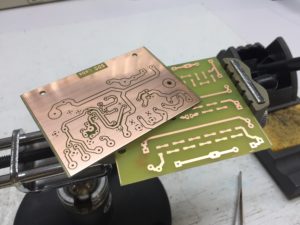

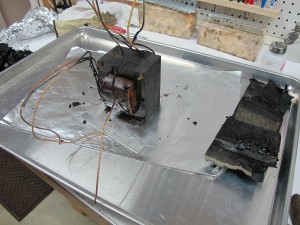

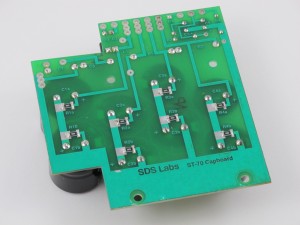

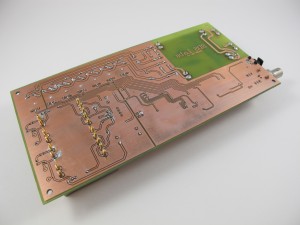

The first step is to suck out as much solder as I could. I took a small oxy-propane torch and a vacuum pump as well as a solder catch can. The catch can is a glass bottle with a plastic lid. I drilled two holes in the plastic lid for two pieces of aquarium tubing. One of the pieces of tubing is hooked to the vacuum pump, and the other piece of tubing is attached to a piece of stainless tubing. The torch is used to locally soften the solder and with my other hand, I would suck it out of the crack with the tubing. The transformer has so much thermal mass, that without a huge torch, there’s no hope of melting the solder all the way around. If I could have added that much heat, I would be risking the transformer insulation. So I relied on localized heating. The photo to the left shows the transformer with the solder sucked out as best as I could. The aluminum foil is actually two layers of foil with a damp paper towel sandwiched between them. This prevents the leads being damaged if I am not careful with the flame.

Shown above is the transformer with the solder removed and I’m in the process of trying to soften the remaining solder so the lid comes off. I’ve switched from the very hot and localized oxy-propane torch to a simple propane torch, which has a much larger and cooler flame. I was hoping that the larger flame would allow more even heating of the seam area and would free the lid. I did some hammering on the seam as well, which I shouldn’t have, but I wasn’t sure if it was press fit or not. It turns out that the solder seam was deeper and more extensive that I had guessed.

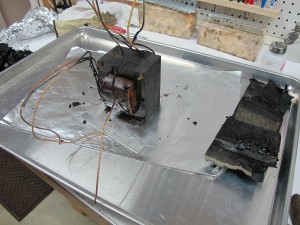

After a lot of heating around the seam area, the transformer can dropped onto the tray with a big thump. My worst fears were realized, it was full of tar, and it smelled awful. With the lid off, I could see that I had more work to do, because the transformer was still stuck in the can under all that tar.

I flipped the transformer over and supported it on the edges of the can using some angle iron. The tar wasn’t coming out at all because the tar at the top (bottom) of the can wasn’t hot enough to be liquid. So I pulled out a third torch, which is a big mapp gas unit with a very broad rosebud type of flame that is ideal for gently heating a large area. As I heated, the guts of the can slowly slid out onto the tray.

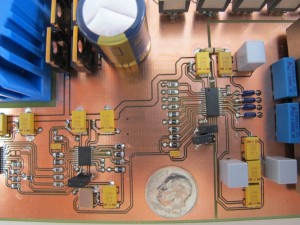

The potting tar doesn’t completely fill the can. The top of the can had no potting compound at all, as apparently most do not. If you tap on the top of a mounted transformer it sounds hollow, an indication that there is no tar on that face. The transformer has a band of insulating paper around it along the long two axes. However, the tar has permeated in around the paper.

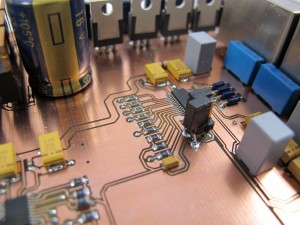

Fortunately, the tar has a nice property, if it’s cold, it’s hard as a rock (too hard to be a good potting compound), and if it’s really hot, it’s a liquid. But in between those temperatures, it’s a soft putty consistency. The process of softening the tar up enough to slide out of the can, left the bulk of the tar in that nice plastic state. It was easy to peel it away from the transformer and it left the transformer really quite clean.

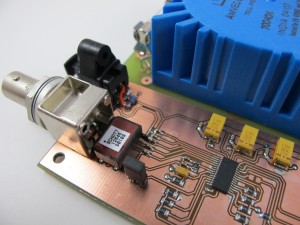

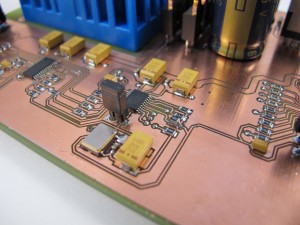

Now it was the moment of truth, time to find the fault. I attached my multimeter to the primary center tap and the offended screen grid lead. The resistance was now about 25 kOhms, a new value. I poked the insulating wrap where the screen grid lead goes in, and bam, open circuit. I poked some more and got another high resistance reading. That was really good news, as the fault was right at the surface. The figure below shows the fault exposed.

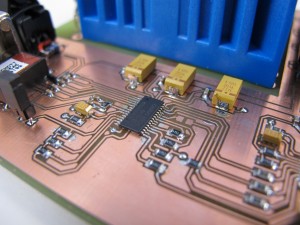

The fault is the transformer copper wire melted away from the stranded wire lead that exits the transformer body. I suspect this is a common fault point because there is a natural air pocket there. The bulk of the windings have a lot of contact area with the neighboring windings and also to the insulating material on either side. But the exit point doesn’t have that luxury for heat transfer, and apparently it overheated and melted back from the contact point. Something serious happened to the screen grid of that output tube. There was some melt products that formed a carbon comp resistor, that I was measuring with my meter before I tore the transformer open. After repairing the joint by cleaning and soldering, it was time to reverse the process. The problem is that the tar was now as hard as a rock.

I taped up the protective paper wrapping that I removed (not as cleanly as I’d have hoped), and formulated a plan for re-potting. My first thought was to set the transformer back in the can, and melt the tar in a pan and pour it back in. I then realized that the can itself makes a dandy pan. So I put all the tar pieces in the can, and set the can on a hotplate set on as low a temperature as it would go. The tar started to soften and I set the transformer on top of the pile of softening tar. As the tar continued to soften, the transformer sunk into the melting tar. I pushed it to the bottom with a stick, and called the re-potting a success. The final steps were to solder the lid back on and to fix the rim where I’d pounded it trying to get the lid off. I filed down the marred areas of the rim, and then bondo-ed the region to smooth it out and hide my butchery.